Strip Clubs, Civics and Real Estate Pt. 1: What Makes a City

After working through various drafts of this blog post for six months, I’ve decided to try publishing it in several parts to make it easier to bring all of the ideas together.

Part 1

If I told you that in most cities in the U.S., the west side of the city is nicer than the east side, would you believe me?

The reason is more surprising—and more logical—than you might assume. To understand the forces at play, it helps to know a little about wind. At various latitudes, wind tends to blow in relatively consistent directions, but those directions differ depending on latitude.

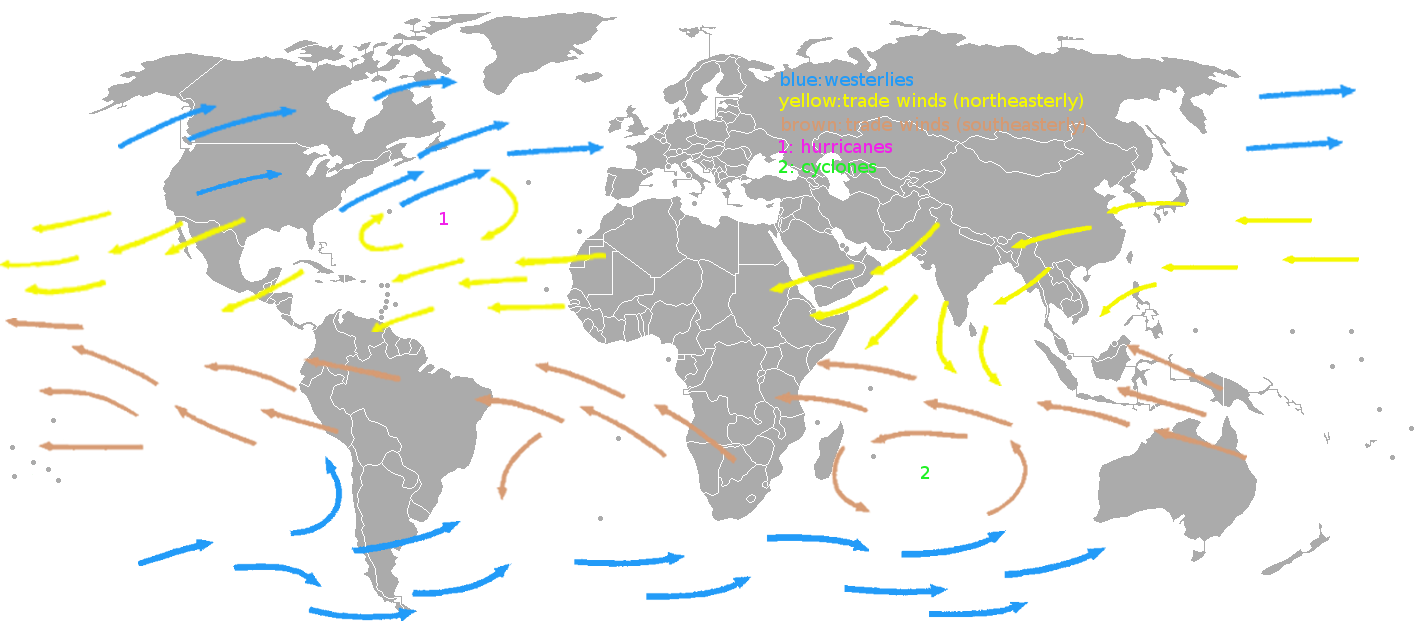

Imagine the globe divided like a four-layer cake, with the North Pole on top and Antarctica on the bottom. In the top and bottom layers—which include North America, Europe, Russia, and the southern tip of South America—wind generally blows from west to east. In the second layer from the bottom—southern Africa and the northern half of South America—wind generally blows from the southeast toward the northeast. In the second layer from the top—China, the northern half of Africa, and Central America—wind generally blows from the northeast toward the southeast.

These patterns exist due to a combination of forces, including differences in surface heating and the rotation of the Earth. Here is a great visual showing the wind directions across the four layers of the cake.

For our purposes, the key takeaway is this: across North America, the prevailing winds blow from west to east.

Now, imagine you are teleported back to Anytown, USA, in 1845. Anytown is home to 15,000 people, most of whom live close to the city center. Most streets consist of plank roads, making inner-city transportation fairly difficult. This incentivizes manufacturers—those producing the goods Anytown’s residents need on a day-to-day basis (coal, meat, textiles, etc.)—to locate their facilities as close to the city center as possible.

Unfortunately, the coal plants and slaughterhouses of Anytown in 1845 produced a noxious array of smells which, thanks to the prevailing westerly winds, were carried eastward. These odors depressed the values of homes located downwind, to the east of the manufacturing districts.

Homes to the west appreciated at a faster rate than homes to the east, leading to greater reinvestment and further price appreciation. By the time these manufacturing facilities were shuttered and replaced with less noxious uses, the quality of the housing stock had diverged enough for the disparity in home values to persist to this day.

As a real estate broker and developer, I was floored the first time I heard this. At a basic level, I already knew that location is a determining factor in home values. If a home commanded a premium because it was built atop a hill with incredible views in 1926, it’s likely that it still has incredible views—and still commands a premium—in 2026.

What was profound about the trade-wind realization was that the original cause of the value difference had been eliminated long ago, yet its effects were still visible today. It made me deeply curious about why our cities are shaped the way they are. What other conditions—natural or manmade—continue to influence how our cities function today?

To be continued.